Take a photo of a barcode or cover

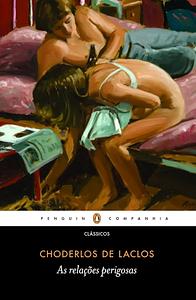

The 1988 movie was true to the book; I can say that now, because having watched the movie umpteen times, I finally got around to reading Laclos' scandalous tale of French society in the 18th century. I imagine it was to the French reader what Fifty Shades of Grey was to the American reader in 2013, except this epistolary novel is well-written.

The story centers around the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, former lovers and now friendly rivals, who seek to outdo each other by manipulating the men and women around them with offers of love and sex. The letters delivered between the characters show the many different faces each person wears, depending on to whom the letters are written.

Originally published in 1782, this novel in four parts reads very easily, and moves quickly. I had no problems comprehending the depths of depravity Merteuil and Valmont were seeking. Laclos also adds footnotes about letters missing, or deemed unnecessary to the plot, which makes them seem to have actually been written and sent.

Highly recommend this "1001 books you must read" selection.

The story centers around the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, former lovers and now friendly rivals, who seek to outdo each other by manipulating the men and women around them with offers of love and sex. The letters delivered between the characters show the many different faces each person wears, depending on to whom the letters are written.

Originally published in 1782, this novel in four parts reads very easily, and moves quickly. I had no problems comprehending the depths of depravity Merteuil and Valmont were seeking. Laclos also adds footnotes about letters missing, or deemed unnecessary to the plot, which makes them seem to have actually been written and sent.

Highly recommend this "1001 books you must read" selection.

I had already seen three adaptations of Dangerous Liaisons prior to reading the novel (Cruel Intentions, the Frears adaptation, and the Hong Kong version) so the reading itself offered little I hadn't already gotten elsewhere (since reading the novel I've seen a fourth adaptation, the Forman version). It's a great narrative though, and I hope they continue to adapt it again and again.

funny

informative

tense

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

A mix

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

Diverse cast of characters:

Yes

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

Baudelaire claimed that Dangerous Liaisons was one of the catalysts for the French Revolution. Marie Antoinette kept a copy by her bed. There have been scores of film and theater adaptations. Clearly, this is an important book. Its fascination is due to the epistolary exchange between the two main characters, the Vicomte de Valmont and the Marquise de Merteuil. They are despicably calculating in their schemes, with no concern for the lives they destroy along the way. These letters are cold, manipulative, intelligent. By contrast, the letters written by and to their victims are tedious and repetitive. I expect the author purposely made such a distinction, but the love letters are so vapid (and also false) that I was tempted to start skimming them! In any case, by the end of the story, the reader is ready for some conclusive action, whether the bent of the reader is toward glorious revenge on the Vicomte and the Marquise for their devilish work, or toward a satisfying success for these two schemers. But the author knows better. He doesn't allow us any satisfaction.

slow-paced

Let’s pretend like I totally didn’t read this book for a very specific reason (Cris telling Joana she loves her by signing it in this book was life changing in May of 2019. The ones that get it, get it!)

I really liked this!! I love a good epistolary novel it was slow and I did have to have a character list for a good 150 pages of it 💀

I really liked this!! I love a good epistolary novel it was slow and I did have to have a character list for a good 150 pages of it 💀

Du pur bonheur, comme seule la langue française de cette époque peut m'en procurer.

dark

funny

tense

medium-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

Yes

Loveable characters:

Complicated

wow!

I vaguely remember this movie, and have wanted to read the book for a long time. I just couldn't get into it though. Not so with this adaptation / play. It will pull you in so quick, and won't let you go. Excellent, excellent production. All the acting/reading is right on. You really won't miss what was cut, this play is right on.

Make up your mind, for I have just received a very pressing invitation from the Comtesse de B . . . . . to go and see her in the country, and, as she writes me amusingly enough, "Her husband has a splendid wood which he carefully preserves for the pleasures of his friends." Well, you know I have some rights over that wood; and I shall go and re-visit it if I am not useful to you.What makes a work of literature a classic? The complacent answer is the dime a dozen frozen dinner version sold in both high schools and 95% of the lists of 'eclectic' readers: the individual answer takes a bit more work. For me, it's a matter of what survives and what does not, not on the merit of never having gone out of print or being repeatedly banned to no avail or riding the rails of academic ivory towers for two and a half centuries longer than it should have, but on whether a human being, with some amount of honest effort and just enough respect for the modern state of literature to know the common patterns of the media's ideologies without necessarily kowtowing to them, reads something and thinks, aha. Humans really haven't changed all that much, have we. When it comes to this particular work, penned by a military man who in governments decadent, revolutionary, and reactionary stood in posts major enough to be written down in historical tract and minor enough to retain him his head, it's easy to cite terminology in abundance from the most obvious of epistolary to the less sure of postmodernism, but what is it about it that makes me think that these controversial pages not only have something timeless about them, but could be easily presented to anyone who is still trying to figure Euro/Neo-Euro with the comment that, here. This goes a fair way into explaining why my kind and I are so fucking weird. It's certainly not what I would have expected from a series of diabolical intercourses set amongst a couple of (supposed) masterminds and their fecund webs of prey, but that's exactly why I continue to bother with this old dead white boys. Every so often, the status quo retains a gem, however much it may have been against their best intentions to do so.

However, the identification of writers with what they write about is more conducive to censorship than to critical understanding. (edition's introduction)Make 'an unstoppable force meets an immovable object' the unspoken law of the land of human beings, and you'll breed monsters the likes of which you'll never see coming. I'm not talking serial killers, but the type who have been granted, by right of the lottery of the birthright, so much excess means of maintaining social stability and who have decided to opt out of the courses of both the dry and dusty hazards of artistic/scientific occupation and that of eating/drinking/STDing themselves to death (many mix and match, of course) in favor of fully enmeshing themselves in the marrow of society as a tape worm latches onto the bowls of its bumbling host. Of course, such is not happening to the utmost degree in a late 18th c. upper class France where the woman are raised as blow up dolls, the men are permitted to be dicks on sticks, but to throw out yet another much abused member of literary terminology, the satire of this work stretches that social machination to such logical reaches as to render it fictionally credible, and then let it all take its tightly laced Russian Roulette to its inevitable completion.

I was in an expansive mood; consequently, before we separated I pleaded Vressac's cause and brought about a reconciliation. The two lovers embraced and I in my turn was embraced by them both. I had no more interest in the Vicomtesse's kisses; but I admit that Vressac's gave me pleasure. We went out together, and after I had received his lengthy thanks we each went back to bed.True, everyone who's not at least slightly evil (as evidenced by his very first letter, the Chevalier Danceny had plenty of abusive/gaslighting tricks up his sleeve long before a certain pair of miscreants got into his head) is rather boring, and the contrast between the rigorous and honestly frightening levels of rhetorical thrust and social manipulation, which have aged almost as well as [b:The Art of War|10534|The Art of War|Sun Tzu|https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1453417993l/10534._SY75_.jpg|3200649] has, and the gothic dramatics that fall out beyond the written page can get rather unbelievable at times. However, Marquise de Merteuil really is a marvel of character creation on par with, if not greater, than Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth, and she is the beating heart of this work that maintains its iron grasp on the reader's willingness to engage with many a long and winding passive aggressive innuendo in a total of 177 letters. And, to follow up on that however with a however, much as we love to love her, Laclos knew better than to ignore the brutal means by which a polite society will naturally recover itself from complete and utter amoral chaos, ending this work on a note that is nothing if not 'There but for the grace of God go I.'

What other girl, coming thus from a convent without experience and almost without ideas, bringing into society (as almost always happens only an equal ignorance of good and evil—what other girl, I say, would have resisted any better such criminal cunning? Ah! To be indulgent it suffices to reflect on how many circumstances, independent of ourselves, depends the dreadful alternative of delicacy or the degradation of our feelings.To see oneself in both the villain and the victim and understand that those who have fallen away along your path are merely yourself with a problem you cannot solve. Human society has come a long way from the days of bundles of written correspondence leading to unsolvable financial ruin and one horse drawn carriage sidling up against another spawning an individual's complete and utter spiritual breakdown, but there's still people out there who think it was just meant to be that certain kinds of white folks were born to rule the roost and that everyone else can get fucked, so if this work is still getting banned, the sexual innuendo isn't the biggest concern (although the queer portions of such were a welcome treat). If Laclos was ever the smartest person in the room, I don't doubt that he always kept such to himself, and if he couldn't easily be called a 'feminist', he certainly had some sort of ironclad sense that women were people and that to judge the characters of 99% of them based on their behavior in public was about as useful as gauging the appearance of dinosaurs solely on the basis of the contours of their fossils. So, not a work where anyone wins, but where a sense of inexorable entitlement meets a will of eternal shrewdness and society gorges itself on the blown up viscera of the aftermath. A bit dramatic, perhaps, but all is fair in love and war until you're the one to pay for it.

And what then have you done that I have not surpassed a thousand times? You have seduced, ruined even, a number of women; but what difficulties did you have to overcome? [...] As to prudence and shrewdness, I do not mention myself—but where is the woman who would not possess more than you? [...] Believe me, Vicomte, people rarely acquire the qualities they can dispense with. You fought without risk and necessarily acted without wariness. For you men defeats are simply so many victories the less. In this unequal struggle our fortune is not to lose and your misfortune not to win. If I granted you as many talents as we have, still how much we would surpass you from the continual necessity we have of using them!

Are you no longer sure of your successes? [...] You want my favours less than you want to abuse your power.