Scan barcode

A review by glenncolerussell

The Diaries of Emilio Renzi: Formative Years by Ricardo Piglia

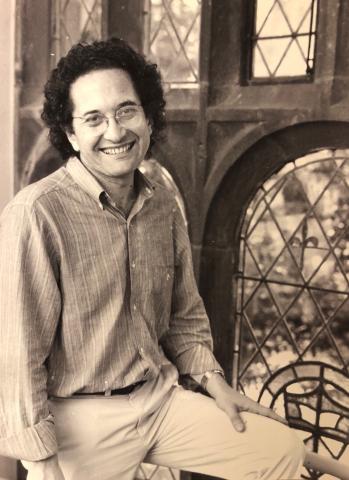

Among the giants of Latin American literature - Ricardo Piglia (1941-2017)

Ricardo Piglia kept a secret journal beginning in 1957 when he was a lad of seventeen, a journal charting his life as a writer by way of his literary alter ego Emilio Renzi.

The Diaries of Emilio Renzi didn't publish until 2015, the year when the author was diagnosed with a terminal illness. The first of three volumes, Formative Years, covers Piglia/Renzi up until 1967.

Here's the thing with these writings: the crossover between fiction and fact, between autobiography and novel is oh so fluid, as if the great Argentine author, very much in the spirit of Jorge Luis Borges and Latin American fabulism, is playing a highly artful game of hide and seek with his reader. Keeping this dynamic in mind, let's turn to actual diary entries:

“He had begun to write a diary at the end of 1957 and continued writing it still.”

So begins the AUTHOR'S NOTE written in 2015 that prefaces the actual diary. Of course, the “he” Ricardo Piglia is referring to is none other than Emilio Renzi.

“How does one become a writer? Is one made to become a writer? For the person that it happens to, it is not a calling, nor is it a decision; it seems instead to be an obsession, a habit, an addiction; if he stops doing it he feels worse but to need to do it is ridiculous, and ultimately it becomes a way of living like any other.”

Many women and men, like myself, don't start writing until later in life. I recall Zoran Živković, Serbia's leading man of letters, citing he doesn't come down hard or offer harsh criticism to young students in his writing class since, you never know – someone could be an outstanding writer but they will not begin to find their voice until they are older. Personally, I'm always impressed with individuals like Philip K. Dick, Samuel R. Delany, Rodrigo Fresán, Bret Easton Ellis and Ricardo Piglia who find their artistic expression and hit their literary stride at an early age.

“His habits, his vices, his own words. Nothing of his interior life, just facts, actions, places, circumstances that, once repeated, created the illusion of a life. An action, a gesture that persists and reappears, saying more than everything that I could ever say about myself.”

Really? Nothing of the author's interior life? While reading, I had the definite sense much of what Ricardo/Emilio presented was very much part of his inner life, which leads me to think these lines were written with Argentina's political and military atmosphere in mind.

“If I can remember the circumstances under which I was with a book, that proves to me that it was decisive. They are not necessarily the best or the ones that have influenced me the most; they are the ones that have left their mark.”

Right from his teenage years, Ricardo Piglia had a deep, abiding relationship with books.

“The value of reading does not depend on the book in itself but on the emotions associated with the act of reading. And often I attribute things to those books that really belong to the passion of that time (which I have now forgotten).

How about that! Ricardo associates a particular book not with ideas so much but with a specific passion the book evoked.

“Popular literature is always educational (that's why it is popular). Meaning proliferates, everything is explained and made clear. On the other hand...there will always be an insuperable rift between seeing and describing, between life and literature.”

So true, Ricardo! I just did finish The Litigators by John Grisham, a hefty 500-page novel where all the characters are fully developed in their clean-cut way. The motives and actions of the main character, a corporate lawyer turned street lawyer, are explained within a legal system where there's a reason for everything and the action unfolds in predictable ways. And there's good reason why a John Grisham novel can be turned into a Hollywood blockbuster, a story where there's none of that murkiness or ambiguity so common in literary novels, especially a Latin American novel where the author is continually playing dodgeball with politics.

I'll conclude by allowing our young author have the last words via these direct quotes:

“To deny reality, to reject what was coming. To this day I still write this diary. Many things have changed since then, but I have remained faithful to this obsession.”

“The only thing that interests me is writing.”

“How to continue a diary that has as its object the delusions of the one writing it and not his real life? First possible reflection: How can we define real life?”

“They suppress everything that can threaten mediocre and average life; they attack diversity in all of its aspects, control it and surveil it, write our biographies. Conformism is the new religion, and they are its priests.”

“Maybe we each have a double, someone the same as us, and also someone who is a replica of one of our friends.”

“The novel works to diverge from a reality that has already been told, and the narrator tries to recall and reconstruct the lives, the catastrophes, the experiences that he has lived through and the things he has been told (for me, things lived through and told about are the same).”