Take a photo of a barcode or cover

This story starts out as a "Let's champion rationality and progressivism in city government" with the story of the rise of power of Mayor John Lindsay, and the lateral rise of power of the Robert McNamara "Whiz-Kids" that helped JFK and LBJ run the Viet Nam war.

And then the story shifts to the difference between "large root-cause fixers of problems," like the power broker Robert Moses and the "small branch-and-twig fixers of problems," like the Tammany/machine street politics found in most big cities.

The hero of the story is, John O'Hagan, who is widely regarded as a giant in the modernization of the fire service in America. But like many great men, hubris and desire for power had unintended consequences.

The victim of the story is New York City, a city whose industrial base hollowed out by zoning, thriving neighborhoods ruined by "urban renewal", and some serious systemic revenue problems.

Thanks to a combination of "big ideas" gone bad, razor-thin budgets, and political disenfranchisement, the NYFD ended up in "The War Years" where fires raged in the Bronx and elsewhere. Despite having the "best and brightest minds" working with the most respected Fire Chief in America. And, according to the author, Because of them.

This is primarily a story of good intentions gone wrong and how focusing on the problem from the wrong angle can make things much much worse. And as a person interested in cities, disasters, and how communities recover, it's a sad tale, well told.

The conclusion offers a story about how cities can thrive _despite_ the mistakes humans make running them. And this makes me feel better. Cities don't suck. They aren't hopelessly flawed. They bounce back from the harm we inflict upon them. Because cities aren't things, they're people, and people are the most flawed, resilient, and tenacious things this world has ever come up with.

Recommended to fans of cities, city politics, and especially fire fighting.

And then the story shifts to the difference between "large root-cause fixers of problems," like the power broker Robert Moses and the "small branch-and-twig fixers of problems," like the Tammany/machine street politics found in most big cities.

The hero of the story is, John O'Hagan, who is widely regarded as a giant in the modernization of the fire service in America. But like many great men, hubris and desire for power had unintended consequences.

The victim of the story is New York City, a city whose industrial base hollowed out by zoning, thriving neighborhoods ruined by "urban renewal", and some serious systemic revenue problems.

Thanks to a combination of "big ideas" gone bad, razor-thin budgets, and political disenfranchisement, the NYFD ended up in "The War Years" where fires raged in the Bronx and elsewhere. Despite having the "best and brightest minds" working with the most respected Fire Chief in America. And, according to the author, Because of them.

This is primarily a story of good intentions gone wrong and how focusing on the problem from the wrong angle can make things much much worse. And as a person interested in cities, disasters, and how communities recover, it's a sad tale, well told.

The conclusion offers a story about how cities can thrive _despite_ the mistakes humans make running them. And this makes me feel better. Cities don't suck. They aren't hopelessly flawed. They bounce back from the harm we inflict upon them. Because cities aren't things, they're people, and people are the most flawed, resilient, and tenacious things this world has ever come up with.

Recommended to fans of cities, city politics, and especially fire fighting.

Stop me if you've heard this story before. In 1960s America, an idealistic reform politician, a young operational technocrat, and the RAND corporation decide to manage a complex social issue via sophisticated data-driven models. For all their vaunted scientific objectivity, the effort collapses into a destructive quagmire that devastates an entire region, kills a whole bunch of non-white people, and wrecks the reputations of everyone involved.

No it's not the Vietnam War, JFK, Robert McNamara, and RAND. It's the South Bronx, Mayor John Lindsay, Fire Chief John O'Hagan, and RAND, and a microcosm of everything that the post-war technocratic liberal order did wrong. Flood orients the story around fire as a central actor in the destruction of the South Bronx, and places the story as part of a broader tide between ad hoc 'branch' approaches to governance which distribute power, and top down 'root' approaches which seek comprehensive theoretically driven explanations.

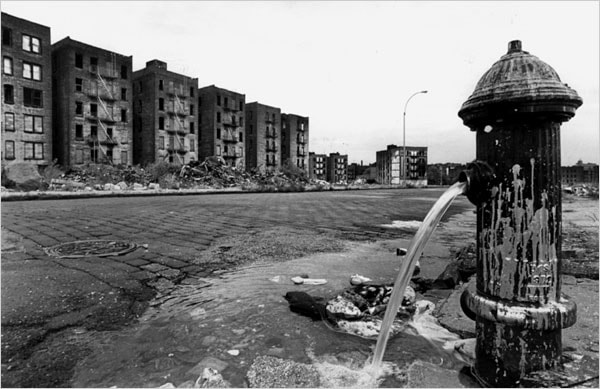

South Bronx, 1971

Lindsay and O'Hagan are the two protagonists of the story. Lindsay was an archetype common enough in New York City politics, the grand reformer, though the details of his liberal Republican to independent conversion are fairly unique. In Flood's analysis, New York City politics waxes in cycles of clubhouse corruption and reformist mayors. The clubhouse, the system of Tammany Hall ward bosses, is opaque, inefficient, unrepresentative, frequently mired in obvious criminality, but accountable to the ordinary people of the city. Reform programs have grand ambitions, but fail to deliver on their promises, prompting a backlash and return to the clubhouses.

O'Hagan was a bit more unusual. A paratrooper in the Pacific in WW2, he joined the NYFD and rose through the ranks, becoming the youngest fire chief in NYFD history, and later one of only two people to simultaneously be Fire Chief and Fire Commissioner. O'Hagan was a tough bastard, a tenacious analyst capable of breaking a problem down into elementary components and assembling a solution. His essay question on the chief's exam, about how to prepare fire safety for the upcoming 1964 World's Fair became the actual plan. O'Hagan introduced new technology, like self-contained breathers, bigger hoses, better ladders, and early version of the hydraulic jaws of life. He obsessed over architectural plans and how to fight fires in the new lightweight steel towers of Manhattan.

In Lindsay's first term, he and O'Hagan worked closely together to find new efficiencies in the fire department. O'Hagan was eager to prove his tough budget cutting credentials to his superiors, and Lindsay needed winds as his administration struggled though labor disputes, rising crime, and race riots. While the situation in the city was not great, much of the chaos was a media exaggeration. New York had almost always been crowded, noisy, chaotic, and with its fair share of crime and corrupt, though the actual numbers were better than the nation's average. The South Bronx was a concern, a mostly Black and Puerto Rican neighborhood with some alarming indicators, but nothing out of the ordinary.

New York had always been able to change with the times, but the difference in 1970 was an ideology of urban renewal which had gripped the city in the prior decades and rendered it extraordinarily fragile. Major commercial streets had been torn out in favor of Robert Moses' grand freeways, whisking people above rather than through neighborhoods. Various administrations deliberately pursued a policy of de-industrialization, eliminating hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs that had served as the first step on the ladder to prosperity for generations of immigrants, just as internal migrants from the Jim Crow South and Puerto Rico arrived. While the housing stock had often been crowded, racist red lining loan policies made it impossible to secure money for basic improvements to apartment buildings in the South Bronx, like a new furnace or roof repairs, and small landlords who lived in and invested in their buildings, a second step to the middle class (and one my family used at about this time) were barred from doing business, leaving housing to parasitic corporate landlords who saw buildings as a rapidly deprecating asset, and the grim public housing of the projects. Finally, one of Lindsay's labor deals had allowed city workers to live in the suburbs, transferring tax dollars out of the city and making fire, police, sanitation, and education a matter of "us vs them" rather than all of us together.

The hollowing out of New York City is complex and multifaceted, a long story with a lot of moving parts that Flood can only partially tell. But the spark was the clever idea to get RAND to find efficiencies in the fire service. RAND was looking to diversify from military contracts as the Vietnam War went sour, and O'Hagan had a suspicion that ordinary fire fighters were slacking off in bull session rather than doing their jobs. Or perhaps on an emotional level, O'Hagan wanted absolute control over the department, and sought to break the old boys networks and union leaders which served as alternative centers.

The situation was a tinderbox, and RAND provided the spark. In an absolute fiasco of applied social science, RAND decided that their primary measure of fire fighting effectiveness was response time between a call and the arrival of a truck on scene. And response time matters, but it isn't everything. A false alarm can be dealt with in minutes, or a simple fire in an up-to-code building with accurate plans. But the dangerous fires are the complex ones: old buildings retrofitted into mazes of room and hidden channels for fire without filed plans. Fire in high rises. Or fires in densely crowded apartment buildings, where hundreds of people might have to be rescued. Unable to quantify workload, RAND went with the simplest proxy.

Worse, their data methodology was horrendously flawed. 14 stop watches were distributed to the hundreds of fire companies, and most of those stop watches went to companies in Manhattan. The data was obviously fiddled with, as most fire fighters considered the whole effort a waste of time that could only harm them. Modelling the complexity of fires proved intractable, so RAND divided the city into seven classes of districts, and only considered adjusting stations in the same class of district. And then O'Hagan adjusted the final recommendation to save politically important stations, the ones near the home of a judge or a congressman.

The end result was that South Bronx lost fire companies just as the population increased and social pressures got worse. The people involved weren't racist per se,. Lindsay was in fact an ardent advocate for civil rights. But O'Hagan regarded apartment fires as technically uninteresting, fire fighters from the outer boroughs as unintelligent, and evaluated the inhabitants of the South Bronx as having the least political influence in the city. A law suit was brought over O'Hagan's closure of South Bronx stations, which was dismissed because the judge glanced at the RAND report and decided that anything with that much math was based on objective science rather than racism.

Fires served as both a leading indicator and a cause of social collapse. While landlord arson made headlines, the majority of fires started as ordinary domestic fires, amplified by the lack of maintenance. And fires in one building caused a rippling decline through the neighborhood. Inhabitants of the building were rendered homeless, and either went to the suburbs, public housing, or squeezing into other overcrowded buildings. Burned out apartments became shelter for junkies and gangs, putting pressure on the remaining honest residents. And junkies nodding off with cigarettes, various people starting fires to stay warm, or bored kids, all burnt semi-abandoned buildings repeatedly, until someone with a can of gasoline put the torched shell out of its misery. One census tract in the South Bronx suffered a 90% population decline between 1965 and 1975 as its housing stock was systematically destroyed.

Any chance that O'Hagan could have recognized the pattern and recovered was stalled by New York's financial crisis of the 1970s. Deficit spending in the previous decade had been covered up with bond measures, and worsening economic conditions finally made the bill due. While liberal welfare policies attracted much of the scorn, a larger share of the burden was tax breaks and developer incentives, such as the ones used to build the World Trade Center, which directly cost the city money through incentives, replaced stable manufacturing jobs with unstable financial services ones, and made existing office space and luxury apartments unprofitable without meaningfully decreasing rents for ordinary people. Every city department needed to make cuts, but O'Hagan had made his first. There was no fat to trim from the fire department, and scarcely any muscle. Any cuts started with bone.

So the South Bronx burned, becoming a byword for urban decay. Lindsay went from a presidential hopeful to one of the most despised mayors in America. O'Hagan resigned as chief and commissioner in 1978, his political ambitions dead, and became a technical consultant on fire fighting. RAND's New York-based urban issues branch was shut down, though RAND-style quantified systems analysis has become the parlance of planning.

The Fires is a persuasive and compelling history, verging onto the polemical. This is not just about New York in the 1970s. This is a valuable lesson about the limits of grand reforms and the dangers of complex models that hide asinine assumptions. Computers have only gotten faster, data more accessible, and many companies are working towards a vision of the smart city, centrally monitored and managed in real time from an urban command center, even if that managerial vision is a dangerous lie. And finally, I live in San Francisco, which feels a lot like New York in the mid 1960s, with a prosperity built on temporary conditions of tech and real estate that create a situation where the city is both too damn expensive and also empty, and where ordinary life flows around a quagmire of human misery the city is unable to fix and so prefers to ignore. And even if you don't live in the city America loves to hate, as the Strong Towns Project has extensively documented, low-density suburbs and exurbs cannot raise enough property taxes to fund infrastructure and services at a level residents expect, leading to a similar version of fragility.

Things haven't started burning yet, but if I smell smoke I'm not sticking around.

No it's not the Vietnam War, JFK, Robert McNamara, and RAND. It's the South Bronx, Mayor John Lindsay, Fire Chief John O'Hagan, and RAND, and a microcosm of everything that the post-war technocratic liberal order did wrong. Flood orients the story around fire as a central actor in the destruction of the South Bronx, and places the story as part of a broader tide between ad hoc 'branch' approaches to governance which distribute power, and top down 'root' approaches which seek comprehensive theoretically driven explanations.

South Bronx, 1971

Lindsay and O'Hagan are the two protagonists of the story. Lindsay was an archetype common enough in New York City politics, the grand reformer, though the details of his liberal Republican to independent conversion are fairly unique. In Flood's analysis, New York City politics waxes in cycles of clubhouse corruption and reformist mayors. The clubhouse, the system of Tammany Hall ward bosses, is opaque, inefficient, unrepresentative, frequently mired in obvious criminality, but accountable to the ordinary people of the city. Reform programs have grand ambitions, but fail to deliver on their promises, prompting a backlash and return to the clubhouses.

O'Hagan was a bit more unusual. A paratrooper in the Pacific in WW2, he joined the NYFD and rose through the ranks, becoming the youngest fire chief in NYFD history, and later one of only two people to simultaneously be Fire Chief and Fire Commissioner. O'Hagan was a tough bastard, a tenacious analyst capable of breaking a problem down into elementary components and assembling a solution. His essay question on the chief's exam, about how to prepare fire safety for the upcoming 1964 World's Fair became the actual plan. O'Hagan introduced new technology, like self-contained breathers, bigger hoses, better ladders, and early version of the hydraulic jaws of life. He obsessed over architectural plans and how to fight fires in the new lightweight steel towers of Manhattan.

In Lindsay's first term, he and O'Hagan worked closely together to find new efficiencies in the fire department. O'Hagan was eager to prove his tough budget cutting credentials to his superiors, and Lindsay needed winds as his administration struggled though labor disputes, rising crime, and race riots. While the situation in the city was not great, much of the chaos was a media exaggeration. New York had almost always been crowded, noisy, chaotic, and with its fair share of crime and corrupt, though the actual numbers were better than the nation's average. The South Bronx was a concern, a mostly Black and Puerto Rican neighborhood with some alarming indicators, but nothing out of the ordinary.

New York had always been able to change with the times, but the difference in 1970 was an ideology of urban renewal which had gripped the city in the prior decades and rendered it extraordinarily fragile. Major commercial streets had been torn out in favor of Robert Moses' grand freeways, whisking people above rather than through neighborhoods. Various administrations deliberately pursued a policy of de-industrialization, eliminating hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs that had served as the first step on the ladder to prosperity for generations of immigrants, just as internal migrants from the Jim Crow South and Puerto Rico arrived. While the housing stock had often been crowded, racist red lining loan policies made it impossible to secure money for basic improvements to apartment buildings in the South Bronx, like a new furnace or roof repairs, and small landlords who lived in and invested in their buildings, a second step to the middle class (and one my family used at about this time) were barred from doing business, leaving housing to parasitic corporate landlords who saw buildings as a rapidly deprecating asset, and the grim public housing of the projects. Finally, one of Lindsay's labor deals had allowed city workers to live in the suburbs, transferring tax dollars out of the city and making fire, police, sanitation, and education a matter of "us vs them" rather than all of us together.

The hollowing out of New York City is complex and multifaceted, a long story with a lot of moving parts that Flood can only partially tell. But the spark was the clever idea to get RAND to find efficiencies in the fire service. RAND was looking to diversify from military contracts as the Vietnam War went sour, and O'Hagan had a suspicion that ordinary fire fighters were slacking off in bull session rather than doing their jobs. Or perhaps on an emotional level, O'Hagan wanted absolute control over the department, and sought to break the old boys networks and union leaders which served as alternative centers.

The situation was a tinderbox, and RAND provided the spark. In an absolute fiasco of applied social science, RAND decided that their primary measure of fire fighting effectiveness was response time between a call and the arrival of a truck on scene. And response time matters, but it isn't everything. A false alarm can be dealt with in minutes, or a simple fire in an up-to-code building with accurate plans. But the dangerous fires are the complex ones: old buildings retrofitted into mazes of room and hidden channels for fire without filed plans. Fire in high rises. Or fires in densely crowded apartment buildings, where hundreds of people might have to be rescued. Unable to quantify workload, RAND went with the simplest proxy.

Worse, their data methodology was horrendously flawed. 14 stop watches were distributed to the hundreds of fire companies, and most of those stop watches went to companies in Manhattan. The data was obviously fiddled with, as most fire fighters considered the whole effort a waste of time that could only harm them. Modelling the complexity of fires proved intractable, so RAND divided the city into seven classes of districts, and only considered adjusting stations in the same class of district. And then O'Hagan adjusted the final recommendation to save politically important stations, the ones near the home of a judge or a congressman.

The end result was that South Bronx lost fire companies just as the population increased and social pressures got worse. The people involved weren't racist per se,. Lindsay was in fact an ardent advocate for civil rights. But O'Hagan regarded apartment fires as technically uninteresting, fire fighters from the outer boroughs as unintelligent, and evaluated the inhabitants of the South Bronx as having the least political influence in the city. A law suit was brought over O'Hagan's closure of South Bronx stations, which was dismissed because the judge glanced at the RAND report and decided that anything with that much math was based on objective science rather than racism.

Fires served as both a leading indicator and a cause of social collapse. While landlord arson made headlines, the majority of fires started as ordinary domestic fires, amplified by the lack of maintenance. And fires in one building caused a rippling decline through the neighborhood. Inhabitants of the building were rendered homeless, and either went to the suburbs, public housing, or squeezing into other overcrowded buildings. Burned out apartments became shelter for junkies and gangs, putting pressure on the remaining honest residents. And junkies nodding off with cigarettes, various people starting fires to stay warm, or bored kids, all burnt semi-abandoned buildings repeatedly, until someone with a can of gasoline put the torched shell out of its misery. One census tract in the South Bronx suffered a 90% population decline between 1965 and 1975 as its housing stock was systematically destroyed.

Any chance that O'Hagan could have recognized the pattern and recovered was stalled by New York's financial crisis of the 1970s. Deficit spending in the previous decade had been covered up with bond measures, and worsening economic conditions finally made the bill due. While liberal welfare policies attracted much of the scorn, a larger share of the burden was tax breaks and developer incentives, such as the ones used to build the World Trade Center, which directly cost the city money through incentives, replaced stable manufacturing jobs with unstable financial services ones, and made existing office space and luxury apartments unprofitable without meaningfully decreasing rents for ordinary people. Every city department needed to make cuts, but O'Hagan had made his first. There was no fat to trim from the fire department, and scarcely any muscle. Any cuts started with bone.

So the South Bronx burned, becoming a byword for urban decay. Lindsay went from a presidential hopeful to one of the most despised mayors in America. O'Hagan resigned as chief and commissioner in 1978, his political ambitions dead, and became a technical consultant on fire fighting. RAND's New York-based urban issues branch was shut down, though RAND-style quantified systems analysis has become the parlance of planning.

The Fires is a persuasive and compelling history, verging onto the polemical. This is not just about New York in the 1970s. This is a valuable lesson about the limits of grand reforms and the dangers of complex models that hide asinine assumptions. Computers have only gotten faster, data more accessible, and many companies are working towards a vision of the smart city, centrally monitored and managed in real time from an urban command center, even if that managerial vision is a dangerous lie. And finally, I live in San Francisco, which feels a lot like New York in the mid 1960s, with a prosperity built on temporary conditions of tech and real estate that create a situation where the city is both too damn expensive and also empty, and where ordinary life flows around a quagmire of human misery the city is unable to fix and so prefers to ignore. And even if you don't live in the city America loves to hate, as the Strong Towns Project has extensively documented, low-density suburbs and exurbs cannot raise enough property taxes to fund infrastructure and services at a level residents expect, leading to a similar version of fragility.

Things haven't started burning yet, but if I smell smoke I'm not sticking around.

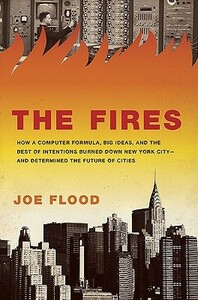

Joe Flood is perhaps the best possible name for the author of a book called The Fires. Or, more completely, The Fires: How a Computer Formula, Big Ideas, and the Best of Intentions Burned Down New York City-and Determined the Future of Cities. That title is a mouthful, but accurately reflects the amazing and diverse subtopics that Flood effortlessly moves back and forth across in explaining the rash of fires in 1970s New York and the decline of the Bronx.

Starting with the machine politics of Tammany Hall and the various city departments’ resistance to reform, Flood traces the ascent of Fire Chief John O’Hagan, a unbelievably intelligent, young reformer in the FDNY with ideas of quantitative analysis in his head. Flood explores the origins of systems analysis and operations research in World War II, and then follows the rise of the RAND Corporation through the early days of the Cold War, and the inexorable meetings between RAND, O’Hagan, and Mayor John Lindsay that led to a radical new firefighting regime citywide.

Sophisticated computer modeling directed the closure of many fire stations throughout the South Bronx, which (unbeknown to me) had been an upscale, classy developed area mostly inhabited by Italians and Jews escaping the slums and tenements of the Lower East Side. As fire after fire engulfed the Bronx, and the fire department proved woefully inadequate at fighting them, a massive phase of white flight began to accelerate. Coupled with Robert Moses’ Cross-Bronx Expressway and Lindsay’s repeal of a city law requiring municipal employees to reside within city limits, the number of whites in the outer boroughs dropped dramatically as they fled to suburban Westchester County and across the river to New Jersey.

Of course, there’s far more than even that to the story. Flood does an absolutely masterful job of weaving together all these disparate threads into a cohesive narrative. There’s Moses and his misguided plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LoMEX), an eight-lane behemoth of an elevated highway that would have utterly destroyed Greenwich Village and much of the surrounding area. The Ford Motor Company and Robert McNamara make an appearance as early benefactors of RAND’s pioneering quantitative research. Flood also gives the rezoning of Manhattan that banished most industry and manufacturing a brief, if absolutely intriguing treatment. He excoriates the weak building codes that existed for much of the twentieth century, and the loophole of the World Trade Center’s construction by the Port Authority that allowed it to skirt New York City building codes.

It’s hard to do The Fires justice. It is so far-reaching – but never over-reaching – that to describe all the different components of its narrative would be impossible without actually writing the book again. But in that sense, hopefully this represents a new trend in historical writing, a truly interdisciplinary effort that never seems to bog down. From sociology to politics to urban planning to history to engineering, Joe Flood just bounces around without getting distracted, but while conveying the sheer complexity of a series of events like this. There’s no single explanation; there are six or seven. It’s an impressive feat.

While this book certainly is a “commercial” history (i.e. no footnotes), it has a wealth of information in the back anyways, using the page-number/quote-fragment system (on another note, does anyone know the actual term for this citation method). Much of Flood’s sourcing consists of personal interviews, giving him a truly first-hand perspective of the events he’s covering. The obscure documents he unearths in some instances also speak to his devotion to the subject. And I know that some of the random tangents he meanders down have given me ideas for a book of my own.

If it’s any kind of testament to the quality of The Fires, not only did I buy it for myself, but I got my father a copy for Christmas. I would buy pretty much everyone a copy of this if they don’t already have it. The Fires is unequivocally recommended by me to anybody who can read.

Starting with the machine politics of Tammany Hall and the various city departments’ resistance to reform, Flood traces the ascent of Fire Chief John O’Hagan, a unbelievably intelligent, young reformer in the FDNY with ideas of quantitative analysis in his head. Flood explores the origins of systems analysis and operations research in World War II, and then follows the rise of the RAND Corporation through the early days of the Cold War, and the inexorable meetings between RAND, O’Hagan, and Mayor John Lindsay that led to a radical new firefighting regime citywide.

Sophisticated computer modeling directed the closure of many fire stations throughout the South Bronx, which (unbeknown to me) had been an upscale, classy developed area mostly inhabited by Italians and Jews escaping the slums and tenements of the Lower East Side. As fire after fire engulfed the Bronx, and the fire department proved woefully inadequate at fighting them, a massive phase of white flight began to accelerate. Coupled with Robert Moses’ Cross-Bronx Expressway and Lindsay’s repeal of a city law requiring municipal employees to reside within city limits, the number of whites in the outer boroughs dropped dramatically as they fled to suburban Westchester County and across the river to New Jersey.

Of course, there’s far more than even that to the story. Flood does an absolutely masterful job of weaving together all these disparate threads into a cohesive narrative. There’s Moses and his misguided plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LoMEX), an eight-lane behemoth of an elevated highway that would have utterly destroyed Greenwich Village and much of the surrounding area. The Ford Motor Company and Robert McNamara make an appearance as early benefactors of RAND’s pioneering quantitative research. Flood also gives the rezoning of Manhattan that banished most industry and manufacturing a brief, if absolutely intriguing treatment. He excoriates the weak building codes that existed for much of the twentieth century, and the loophole of the World Trade Center’s construction by the Port Authority that allowed it to skirt New York City building codes.

It’s hard to do The Fires justice. It is so far-reaching – but never over-reaching – that to describe all the different components of its narrative would be impossible without actually writing the book again. But in that sense, hopefully this represents a new trend in historical writing, a truly interdisciplinary effort that never seems to bog down. From sociology to politics to urban planning to history to engineering, Joe Flood just bounces around without getting distracted, but while conveying the sheer complexity of a series of events like this. There’s no single explanation; there are six or seven. It’s an impressive feat.

While this book certainly is a “commercial” history (i.e. no footnotes), it has a wealth of information in the back anyways, using the page-number/quote-fragment system (on another note, does anyone know the actual term for this citation method). Much of Flood’s sourcing consists of personal interviews, giving him a truly first-hand perspective of the events he’s covering. The obscure documents he unearths in some instances also speak to his devotion to the subject. And I know that some of the random tangents he meanders down have given me ideas for a book of my own.

If it’s any kind of testament to the quality of The Fires, not only did I buy it for myself, but I got my father a copy for Christmas. I would buy pretty much everyone a copy of this if they don’t already have it. The Fires is unequivocally recommended by me to anybody who can read.

Thoroughly satisfying as a nerd-lite descent into the perils of trying to use statistical analysis to to turn societal ills into algebra. Veers into repetitiveness a few too many times in the middle, but what I liked most was the picture it painted of a moment in time when a small group of people's individual blind spots all happened to align, for different reasons, on the same spot (the Bronx) with catastrophic consequences.

This story of how a bunch of know-it-all nerds juggled some numbers and burned down the best parts of NYC filled me with rage. Flood -- a Bronx native -- tries for an evenhanded, no bad guys approach, but when there are overtly racist motivations at work he doesn't shy away from describing them. Although he is trying to simply be critical of certain approaches to governance and avoid conspiracy theory weirdness, I was left thinking that a bunch of bad people orchestrated a decades long ethnic cleansing program in my grandparents' neighborhood. Flood uses the oxymoron "free market" a little too often for me, but his general point feels right: that systems that gather knowledge and solutions from the bottom up and with an "entrepreneurial spirit" are less capable of large scale destruction than top-down grand planner hierarchies, and that both are prone to corruption.

There is a warning here for all the people currently enamored with "big data" and "data mining" ... these mostly white boy tech-heads are just going to justify their racist and sexist garbage with a bunch of crap numbers they pulled out of their butts, claiming, "I am not racist, the computer says this is the right thing to do... and if it harms people of color... all the better..." well, sorry, but that's basically what happened when they let the Bronx burn and the same kinds of jerks are working on the same kind of evil today. But that's me, Flood is much more chilled out about the whole thing.

I wanted to read this book because the fires and the fiscal crisis of 70s NYC are the context for true school hip hop and Fania salsa. But this is mostly about the planners and the jerks at RAND and the firefighters and not so much about the people of the Bronx... although the founders of hip hop get a mention in the conclusion.

There is a warning here for all the people currently enamored with "big data" and "data mining" ... these mostly white boy tech-heads are just going to justify their racist and sexist garbage with a bunch of crap numbers they pulled out of their butts, claiming, "I am not racist, the computer says this is the right thing to do... and if it harms people of color... all the better..." well, sorry, but that's basically what happened when they let the Bronx burn and the same kinds of jerks are working on the same kind of evil today. But that's me, Flood is much more chilled out about the whole thing.

I wanted to read this book because the fires and the fiscal crisis of 70s NYC are the context for true school hip hop and Fania salsa. But this is mostly about the planners and the jerks at RAND and the firefighters and not so much about the people of the Bronx... although the founders of hip hop get a mention in the conclusion.

"Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning."

Howard Cosell never said this in 1977, but the Bronx surely burned. I read, before, that the fires of 1970s New York were an arson plot, designed to burn out tenants and get rid of unprofitable buildings. Flood convincingly demonstrates that this was largely not the case—most buldings were not burned by arson, and the arson that did occur was largely buildings that had already been abandoned. Instead, the fires were the culmination of a long series of events, largely tied to changes in New York politics and the use of centralized planning and root analysis.

There is an enormous amount of information in this book, most of which is not about the fires themselves. That was slightly disappointing, as I would have been interested to read more about the fires and their effects. Flood doesn't even get to the fires until page 172, and spends the first half-plus of the book setting up his chess pieces. There's far too much to summarize: The tension between Tammany Hall's machine and would be reformers; Mayor Lindsay, who campaigned as one of those reformers after a particularly corrupt stretch; Fire Chief and later Commissioner Joe O'Hagan, who is determined to modernize the department; and the social changes of the 1960s.

When discussing the history of New York and the consequences of urban planning, there's a tendency, which Flood sometimes falls prey to, to romanticize the days of Tammany Hall and the chaos of the slums. Tammany was a corrupt organization that harmed as many as it helped, and as New York diversified, it maintained its Irish-Italian base, closing out Black and Puerto Rican politicians. There's solid reasons that reform mayors have been periodically elected, especially Fiorello LaGuardia. The city's elite made catastrophic decisions to de-industrialize early, to remove working class neighborhoods, and to treat ordinary New Yorkers as chess pieces that could be moved at will. But we need to remember that the old neighborhoods (that my grandparents grew up in) were not all lovely places, and the street ballet that Jane Jacobs memorably described is one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the city and has been for decades. Flood does, to his credit, acknowledge Tammany's corruption, but it would be better to appreciate its street level organization without liking the organization that created it. By the late 1960s, city politicians, of both parties and all races, were willing to sell out their constituents, making them ineffective counterweights to bad planning.

Flood is on sure ground when he examines the specific flaws of root analysis. Data is useful (the initial CompStat program grew out of a real need, as he points out), but a model is only as good as the data it's given. RAND used data that didn't correlate well to outcomes, and then politicians manipulated it. The result was that units in the busiest areas were cut, making the fires harder and harder to combat. When fiscal crisis hit in 1975, O'Hagan's efficiency bit him: his department had no fat to cut.

This is, overall, a great read about how the pieces of history combined to create a crisis that destroyed large swathes of NYC and displaced hundreds of thousands. Flood wrote this at the tail end of the Bloomberg administration, which was infamous for its centralized, data focused approach, and I can't help but think that this is meant as a retort. In the end, however, we should not view it as a simple binary choice. Planning is useful. Data, when used carefully and thoughtfully, is important: our instincts can fail us. But the story of the fires warns us about the consequences of a root analysis that's done by people with little street level familiarity; who treat a social problem as a mathematical abstraction.

Howard Cosell never said this in 1977, but the Bronx surely burned. I read, before, that the fires of 1970s New York were an arson plot, designed to burn out tenants and get rid of unprofitable buildings. Flood convincingly demonstrates that this was largely not the case—most buldings were not burned by arson, and the arson that did occur was largely buildings that had already been abandoned. Instead, the fires were the culmination of a long series of events, largely tied to changes in New York politics and the use of centralized planning and root analysis.

There is an enormous amount of information in this book, most of which is not about the fires themselves. That was slightly disappointing, as I would have been interested to read more about the fires and their effects. Flood doesn't even get to the fires until page 172, and spends the first half-plus of the book setting up his chess pieces. There's far too much to summarize: The tension between Tammany Hall's machine and would be reformers; Mayor Lindsay, who campaigned as one of those reformers after a particularly corrupt stretch; Fire Chief and later Commissioner Joe O'Hagan, who is determined to modernize the department; and the social changes of the 1960s.

When discussing the history of New York and the consequences of urban planning, there's a tendency, which Flood sometimes falls prey to, to romanticize the days of Tammany Hall and the chaos of the slums. Tammany was a corrupt organization that harmed as many as it helped, and as New York diversified, it maintained its Irish-Italian base, closing out Black and Puerto Rican politicians. There's solid reasons that reform mayors have been periodically elected, especially Fiorello LaGuardia. The city's elite made catastrophic decisions to de-industrialize early, to remove working class neighborhoods, and to treat ordinary New Yorkers as chess pieces that could be moved at will. But we need to remember that the old neighborhoods (that my grandparents grew up in) were not all lovely places, and the street ballet that Jane Jacobs memorably described is one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the city and has been for decades. Flood does, to his credit, acknowledge Tammany's corruption, but it would be better to appreciate its street level organization without liking the organization that created it. By the late 1960s, city politicians, of both parties and all races, were willing to sell out their constituents, making them ineffective counterweights to bad planning.

Flood is on sure ground when he examines the specific flaws of root analysis. Data is useful (the initial CompStat program grew out of a real need, as he points out), but a model is only as good as the data it's given. RAND used data that didn't correlate well to outcomes, and then politicians manipulated it. The result was that units in the busiest areas were cut, making the fires harder and harder to combat. When fiscal crisis hit in 1975, O'Hagan's efficiency bit him: his department had no fat to cut.

This is, overall, a great read about how the pieces of history combined to create a crisis that destroyed large swathes of NYC and displaced hundreds of thousands. Flood wrote this at the tail end of the Bloomberg administration, which was infamous for its centralized, data focused approach, and I can't help but think that this is meant as a retort. In the end, however, we should not view it as a simple binary choice. Planning is useful. Data, when used carefully and thoughtfully, is important: our instincts can fail us. But the story of the fires warns us about the consequences of a root analysis that's done by people with little street level familiarity; who treat a social problem as a mathematical abstraction.

U.S. government research and development computer modeling -- spun off as the RAND Corporation think tank -- drives military prowess and Robert McNamara's Vietnam War, then intervenes at Ford Motor Co., and on those "successes" ends up promulgating changes in the city government of New York with the fire department as a test case.

Except the changes rammed through city hall subverted the common sense intelligence of those on the front-lines -- specifically, the firemen and NYC's most progressive commissioner/chief, John O'Hagan -- and helped devolve the (arguably) greatest city in the world into a disintegrating, dangerous, fire-ravaged, feared "city in crisis" that was nearly lost to myopic bureaucracy.

In this well-researched, rich-in-details book by the young and wonderfully talented Joe Flood ((http://joe-flood.com/reviewsandmedia)), a post-war history is revealed of a city struggling through financial bungles, political gamesmanship and racial rifts in the '60s and '70s.

Of all the books I've read in the past several months, this is a standout. It is not only about the fires of the South Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan's Lower East Side and Harlem, and how poor neighborhoods were allowed to burn down through practically purposeful neglect, but also about the history of the city's dysfunction -- beginning with the corrupt Tammany Hall and political "clubhouses," and through to the political subversion of fire codes that allowed deathtraps such as the World Trade Center towers to exist -- and how an experiment in social and civil engineering based on flawed assumptions and bad mathematical models was exported to cities across the country.

If you thought NYC was being torched by arsonists at every turn during those years, this book will give you perspective on what was really behind the city that burned.

Includes a serviceable history of the tenures of Mayors La Guardia, Lindsey and Beame.

Except the changes rammed through city hall subverted the common sense intelligence of those on the front-lines -- specifically, the firemen and NYC's most progressive commissioner/chief, John O'Hagan -- and helped devolve the (arguably) greatest city in the world into a disintegrating, dangerous, fire-ravaged, feared "city in crisis" that was nearly lost to myopic bureaucracy.

In this well-researched, rich-in-details book by the young and wonderfully talented Joe Flood ((http://joe-flood.com/reviewsandmedia)), a post-war history is revealed of a city struggling through financial bungles, political gamesmanship and racial rifts in the '60s and '70s.

Of all the books I've read in the past several months, this is a standout. It is not only about the fires of the South Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan's Lower East Side and Harlem, and how poor neighborhoods were allowed to burn down through practically purposeful neglect, but also about the history of the city's dysfunction -- beginning with the corrupt Tammany Hall and political "clubhouses," and through to the political subversion of fire codes that allowed deathtraps such as the World Trade Center towers to exist -- and how an experiment in social and civil engineering based on flawed assumptions and bad mathematical models was exported to cities across the country.

If you thought NYC was being torched by arsonists at every turn during those years, this book will give you perspective on what was really behind the city that burned.

Includes a serviceable history of the tenures of Mayors La Guardia, Lindsey and Beame.