You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

I read it in two days. I couldn't put it down, and it's going to stay with me for days. I'll dream about it. It's also confirmed my desire to see the Killing Fields in Cambodia before 2015 is over.

A beautifully written book about the grossest of subjects; the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia. The language and images float like spider silk, even as they describe the atrocities committed against a people. Orwell's "1984" is a book about totalitarianism, but it left me the reader on the outside looking in; Thien's book is a novel, but it reeks utterly of real people whose lives get snuffed out.

The book traces the splintering of family relationships under the ideology of the "Year Zero" return to a clean sheet for society. it also traces the splintering of the individual, as psyches are assaulted first by being cut adrift from others, then having to survive bodily the harshest of privations and then identities are deliberately stripped away as people are renamed and forcibly made to ascribe to the ridiculous sayings of "Angkar", the Khmer Rouge's authoritarian "Organisation". The sayings are part Marxism, part Buddhism and part nonsense. They are empty boasts from the very get go of the revolution. " I looked at the sky, at the trees, at the disturbed mound of earth and saw no possible gods". An agricultural people stripped from their spiritual atachment to the land through turning them into killing fields of dead bodies.

The reason I give this book 4 stars rather than 5 is because it sets up a potentially fascinating image, since the two main protagonists who have remade new lives in Montreal are both scientific researchers of the human brain. They engage with it at an electro-chemical level, stimulating the neurons, breaking down everything into the constituent chemical reactions. implicit in this is that human emotions too are just chemical reactions, including the suffering and emotional turmoil that plays merry hell with memory- what we retain, what we lose. But this theme is never really returned to, and the future lives of the two characters at the start of the book, remains an untapped resource for its bulk.

Still, an outstanding read. I have read a lot of history books on the period, but it takes a damn fine novel to really bring home the atrocity and its scale.

The book traces the splintering of family relationships under the ideology of the "Year Zero" return to a clean sheet for society. it also traces the splintering of the individual, as psyches are assaulted first by being cut adrift from others, then having to survive bodily the harshest of privations and then identities are deliberately stripped away as people are renamed and forcibly made to ascribe to the ridiculous sayings of "Angkar", the Khmer Rouge's authoritarian "Organisation". The sayings are part Marxism, part Buddhism and part nonsense. They are empty boasts from the very get go of the revolution. " I looked at the sky, at the trees, at the disturbed mound of earth and saw no possible gods". An agricultural people stripped from their spiritual atachment to the land through turning them into killing fields of dead bodies.

The reason I give this book 4 stars rather than 5 is because it sets up a potentially fascinating image, since the two main protagonists who have remade new lives in Montreal are both scientific researchers of the human brain. They engage with it at an electro-chemical level, stimulating the neurons, breaking down everything into the constituent chemical reactions. implicit in this is that human emotions too are just chemical reactions, including the suffering and emotional turmoil that plays merry hell with memory- what we retain, what we lose. But this theme is never really returned to, and the future lives of the two characters at the start of the book, remains an untapped resource for its bulk.

Still, an outstanding read. I have read a lot of history books on the period, but it takes a damn fine novel to really bring home the atrocity and its scale.

The first three-quarters of this was mesmerizing. It was poignant and haunting, with beautiful descriptions of the limits of human grief. Then it degenerated into navel-gazing absolute sadness.

I loved this book. I felt it had something to say about the world. It was great for filling in my knowledge about Khmer Rouge and Cambodia, but mainly because it is beautifully written and completely compelling. I had to keep stopping myself from reading it all at once to try to make it last longer

This story offers a child's eye view of the Khmer Rouge and the devastating effects on Cambodia. Beautifully poetic prose, it is hard to follow at times as the story weaves between times and identities. A story where past and present are so utterly interlinked, I found it far more gripping than I initially thought I would and read it in just 2 days.

The first part gave me nightmares & was heartbreaking. I waited a while & finished the book but wish I hadn't. I found it disjointed & full of suffering throughout.

Tragic but necessary. Different perspectives on a totalitarian government and the tumbles of being a refugee. Sad but poetic and reads like an intimate look into the lives of the displaced.

reflective

medium-paced

Thien's grasp of threads is immediately disarming. The initial chapters invite you into a warm pool of confusion, of loss, of missing pieces. As the story progresses, as "Mei" recounts her childhood being ripped from her under the Khmer Rouge communism, Thien's true talents as a storyteller take hold. "Mei" alludes to the life that her family had before the end of the war, before the Khmer Rouge dismantles their city and steals her away from her possessions. But it is the lives they try to live -- the debunked hospitals that they must enter, and the shallow graves they must ignore and all at once embrace -- in Year Zero, in the new regime, that grabs you by the throat. The numerous lives she and her brother, and even her mother, must lead are all so arbitrary, and yet all so integral to their survival. While we hear only what she knows of her father's disappearance, into the back of a truck to be sent for further "education," we are given a dose of what that reality may have been through King James. Hundreds of thousands, millions, whatever the number bleeds into, there are so many lives ripped apart and sewn back together again in the light of the new, hostile, suspicious regime. Soldiers build themselves out of dirt, shedding the capitol of their pasts, only to be thrown to the newer, bigger, hungrier wolves that rise up from the jungle. Despite the commitment to cleansing, to purification, to attaining equality by denouncing your family, your ancestry, your past, each and every one of us holds out hope that the threads of our hearts still exist, still billow in the wild wind, and that we may some day find them again.

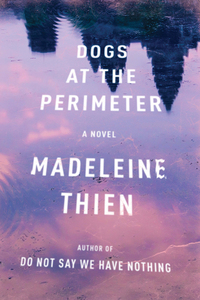

Feels like a pseudo-blueprint for Do Not Say We Have Nothing, but that impression probably results from blitzing through this less than 48 hours after finishing the other, and it's really a disservice to both, suggesting Dogs at the Perimeter is a dress rehearsal. They explore similar themes, rendered in clear prose, but that's the extent of it. There's an uncompromising starkness to this earlier work that the more recent one lacks, making Dogs less immediately accessible, and ultimately better at conveying the conflicted reality of forging identity in the wake of personal and historical trauma.